Journal of Unification Studies Vol. 18, 2017 - Pages 139-156

Unity of knowledge is one of the central theses of Unificationism. This article is a preparatory analysis to explore the methodology with which one can approach this unity from a Unificationist perspective.[1] In this article I use hermeneutics, a theory of interpretation, to present a multidimensional approach to the integration of knowledge. I highlight how such an approach allows collaboration among disciplines while retaining the autonomy and integrity of each discipline. I also explore two types of hermeneutical approaches, the transformative and the objective that are typically present in religion and science respectively, and explore these perspectives through the concept of truth in the Divine Principle. The article is an attempt to develop Unification Thought by taking a hermeneutical approach, in order to explore an alternative philosophical approach in Unificationism.

When Rev. Sun Myung Moon initiated the International Conference on the Unity of the Sciences (ICUS) in 1972, he presented the “unity of knowledge” and “science and values” as guiding ideas for this interdisciplinary forum.[2] He envisioned various kinds of unity including the unity of religions, the unity of science and religion,[3] as well as the unity of natural, social, and human sciences. The question is: what kind of unity does Unificationism envision, and how is it possible?

Unification Thought (UT), a philosophical exposition of Unificationism developed by the late Dr. Sang Hun Lee,[4] presents itself as a unified thought system and shows how various fields of philosophy, including ontology, epistemology, ethics, theory of history, and others, are integrally connected on theistic grounds. The focus of UT, however, seems to remain an exposition of how key Unification concepts can be applied to diverse philosophical fields. In other words, Dr. Lee tried to show how the same key concepts of the Divine Principle can be applied to ontology, epistemology, ethics, and other philosophical fields. Dr. Lee’s approach appears to be similar to pattern recognition, taking key Unification concepts as the patterned schema, and Dr. Lee’s effort was to find identical schema to describe diverse fields. UT, however, does not critically analyze its own approach and does not attempt to justify its approach or explore its own limits.

Philosophy is a self-reflective and self-critical discipline. Such self-criticism leads to an articulation of its own undertaking and justification to its approach. Currently, UT lacks this element. While it presents key Unificationist concepts and how they are uniformly applicable to diverse phenomena, it does not adequately articulate its approach, explain why its approach is appropriate, and explore its own limitations. In a word, it lacks self-reflection.

If we want to develop a philosophical work within Unificationism, we need to take a self-critical, self-reflective approach. Such an approach will enable us to recognize a range of issues that UT currently does not address, including the philosophical methodology of the Principle, the relationship between faith and reason or freedom and determinism, the existence of God and the afterlife, and others. A critical stance allows us to bring implicit presuppositions to the foreground and subject them to critical scrutiny, thereby opening the door to new Unificationist insights on those issues.

Is it possible to develop a philosophical treatise of Unificationism that goes beyond the approach of pattern-recognition? Considering the goal of the unity of knowledge, we need to consider an approach that can integrate methodologically different disciplines.

Among possible approaches, I take the hermeneutical approach in this article. Since each theory or discipline presents its own interpretive framework, the integration of knowledge means the integration of multiple interpretations. In other words, the task of the integration of knowledge entails the hermeneutics of hermeneutics, or the construction of an interpretive framework for multiple interpretations. The unity of knowledge is not simply conflating knowledge by eliminating the distinct advantages and values of diverse disciplines. Rather, the task is to develop a framework to allow for the creative collaboration of diverse forms of knowledge

Although there are overlaps and crossovers among disciplines, each discipline is more or less demarcated by its methods and the standards it uses to validate knowledge, norms of practices, types of rigor, and other criteria. Thus, when Unificationism presents the idea of the unity of knowledge, questions arise: What kind of unity does it envision when considering the wide range of differences in methods? How might this unity be possible?

While the quest for the unity or integration of knowledge has been a recurring theme in the history of philosophy,[5] there always is the question of the approach. In this article, I explore a multidimensional hermeneutical approach. Its task is three-fold: 1) to articulate what we mean by unity; 2) exploring why and how, through such an approach, widely differing disciplinary forms can retain their integrity; 3) how Unificationism can frame this approach.

The Quest for Meaning as the Fundamental Human Drive

One of the most fundamental drives or urges in human life is the quest for meaning. The question of meaning is so fundamental that it exits underneath all human activities, both personal and social, and it extends to the very existence of human beings from birth to death and beyond. The quest for meaning is intrinsic to the existence of human beings and drives and guides human understanding. When we assess scientific theories, religious beliefs, and philosophical perspectives, we naturally ask: “Does it make sense?”

Our cognitive endeavors move from comprehension to analysis, appli-cation, and all the way to synthesis and assessment. Regardless of cognitive levels and types, whether something makes sense is a critical factor in human understanding. We choose and configure frameworks of interpreta-tion, which makes the best sense of given phenomena. A worldview is the natural outcome of our efforts to find a coherent and consistent framework of interpretation for our private and collective experiences of life.

We can see each scientific theory and religious faith as an attempt to give a coherent and consistent interpretation of specific phenomena seen from a particular perspective. As I will discuss later, each interpretation is necessarily perspectival and partial. Our quest for meaning is, however, driven by a desire to integrate various interpretations. In other words, while each interpretation is perspectival and partial, it has an internal impetus to go beyond itself and seek a more comprehensive interpretation. The idea of unification in Unificationism can be construed as this impetus for a comprehensive, integral framework of interpretation.

The Relational Nature of Meaning: Part-whole Relationships

How Do Meanings Arise?

When we find some item, claim, or event that does not fit the whole theory or your general framework of understanding, you will say, “this does not make sense.” Meaning is a relational concept, and it arises from its relation to the whole. For example, when you encounter a devastating event, you try to find a way to fit it into your worldview. When you can find a way to contextualize it in your worldview and the narrative of your life, you can “understand” and the event can “make sense.” You may even seek another worldview if the event or experience demands a better explanation.

One of the most fundamental principles of hermeneutics, the theory of interpretation, is the part-whole relationship. The meaning of a part arises out of its relationships with the whole. For example, the meaning of a word arises from its relationship with the phrase, sentence, syntactical and semantic totality of the given language; the language is further contextualized within social, cultural lives or the “life-world” (social, cultural, and historical life contexts). Thus, the meaning of a word changes according to its relationships with layers of contexts within language and its extra-linguistic life-world. Ludwig Wittgenstein saw the meaning of the word in its use: “For a large class of cases of the employment of the word ‘meaning’—though not for all—this way can be explained in this way: the meaning of a word is its use in the language.”[6] The meaning of an item or event (a part) thus depends on its context (the whole).

Multiplicity of Part-Whole Relationships

Every being exits within matrices of part-whole relationships. Accordingly, each being has multiple meanings according to its relationships with its contexts (wholes). For example, water is a vital resource for growth of crops for farmers, or it can be holy in a Christian baptism. For firefighters, water is a means to put out a fire. Multiple meanings of an item arise out of various teleological relationships. Some items, such as a nail clipper, have a specific purpose and narrow range of uses; other items, such as water, have a wide range of potential uses.

Meaning, however, can be much broader than its original purpose and usage. For example, if your nail clipper is the one your mother used to cut your nails in the early years of your life, it has a special meaning for you. A simple nail clipper exists within layers of contexts; even if it is broken and practically useless, the meaning of the nail clipper remains within the context of life. If you cut your child’s nails and give the clippers to your child, the nail clipper is interwoven into the fabric of your child’s life and comes to have another layer of meaning.

The meaning of an item (part), be it an experience, event or thing, arises from its relationships with its contexts (wholes; social, cultural, historical contexts; worldviews, etc.) Because the same item exists in multiple layers of contexts, its meaning unveils multilayered phenomena open to further expansion.

Meaning as Open-Ended: Spatial and Temporal Perspectives

The meaning of an item (part) is open to further expansion in two ways, spatial and temporal. For example, the meaning of an event in your life is seen from multiple layers of contexts (whole). It can have different meanings within the context (whole) of your spouse, community, social-cultural groups, and so on. Its meaning expands spatially beyond an individual life context to larger social, cultural, and historical contexts.

As for temporal expansion, consider that the context of a life, be it individual or in social groups, is in principle open to the future. Consider your life as an example. Your life narrative may be divided into several periods like the chapters of a book: childhood, teenage years, adulthood, and so on. An event in your teenage years, for example, has a certain meaning within the context of that chapter. As life has its twists and turns, the meaning of events or experiences in your life is open to further meaning as your life develops. Your life context extends indefinitely into the future until you die, and even after your death you may leave a legacy for those who are yet to come. Thus, meaning is a spatially and temporally open phenomenon.

The Perspectival Nature of Interpretation

Interpretation is necessarily perspectival, and meaning arises from interpretation. Human beings interpret an item, be it the self or an object of scientific inquiry, from a particular perspective. Phenomena disclosed through one’s perspective are, therefore, necessarily partial and limited. Because of these limitations of human understanding, it is possible for us to progressively learn from one step to the next. If human beings had access to infinite perspectives at once, there would be no such thing as learning or discovery. The perspectival nature of human understanding makes it possible for us to learn, grow, and discover.

Perspective raises the question of relativism. If human understanding is rooted in a perspective, does it necessarily lead to relativism? Although no view is final and exhaustive, not all views are equal in plausibility and certainty. The power of explanation differs from perspective to perspective according to logical consistency and coherence, and supportive and experiential evidence; some views prevail over other according to the degree of plausibility.

Validation of Knowledge and Relative Autonomy and Integrity of Discipline

Perspective pertains to the autonomy and integrity of academic disciplines. Although there are multiple competing theories and perspectives in each discipline, each academic community defines and establishes rules, procedures, and criteria to preserve its own integrity. Although the demarcation of valid and invalid knowledge is not necessarily always clear, the academic community works as a guardian of knowledge in each discipline. The reliability of knowledge is sustained by the communal efforts of those maintaining the standards of their practices. There are varying degrees of acceptance among validation mechanisms, and commonly accepted ones become standard. In some cases, competing theories with different assumptions can co-exist as recognized theories if they meet certain standards. Although such practices are not perfect, recognition by communities of scholars is indispensable in establishing the validity of knowledge.

A Multi-Dimensional Approach: The Hermeneutics of Hermeneutics

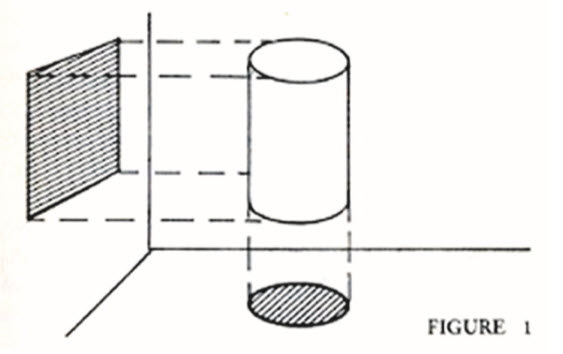

This perspectival nature of interpretation leads to a multidimensional approach, which I will explain using illustrations from Viktor Frankl. Any theory is built on certain assumptions and presuppositions, which set the horizon, the limit, of what it can see. Within its own limited framework, each theory presents given phenomena from a particular perspective. Hence, its knowledge is necessarily partial and limited. In The Will to Meaning: Foundations and Applications of Logotherapy, Frankl illustrates how reality, whatever it is, is projected differently onto a plane: “One and the same phenomenon projected out of its own dimension into different dimensions lower than its own is depicted in such a way that the individual pictures contradict each other.”[7]

The projected images, a circle and square in this illustration, are contradictory. Nevertheless, they are true to their perspective. This illustrates how competing theories can present contradictory images of the same reality because of the perspectival nature of interpretation.

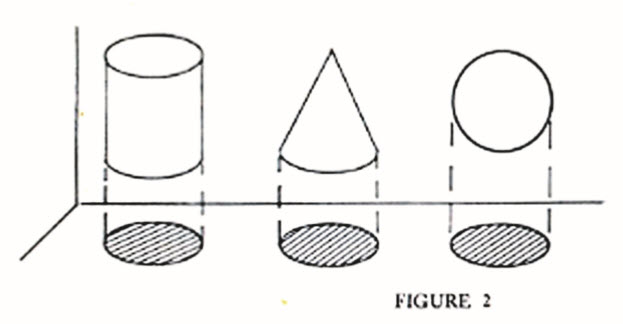

Frankl also illustrates the ambiguity of projected images: “Different phenomenon projected out of their own dimension into one dimension lower than their own are depicted in such a manner that the pictures are ambiguous.”[8] In the example below, all the projected images are circles. The real objects, however, are quite different: a cylinder, a cone, and a sphere. Projected images do not tell such different realities. Frankl also notes that if a cup is projected onto a plane it can appear as a circle or cylinder, but without an opening. In the psychotherapeutic field that Frankl specialized in, psychiatrists may observe the same symptoms from one theoretical perspective; however, the real issues underlying these symptoms can be quite different. We can realize such differences only when we see the patient from multiple perspectives.

Frankl presents these illustrations in order to illustrate his “multi-dimensional ontology” approach to psychotherapy. He argues that while Freud approached human psyche from a bodily perspective and Adler from a mental perspective, he presents a three-dimensional approach incor-porating body-mind-spirit. Yet even though he points out the limitations of the Freudian and Adlerian models, he does not present his approach as a universally applicable theory. He rather advocates for multiple approaches to mental health.

Frankl remarks on the limitation of science and the need for a multidimensional approach:

Science cannot cope with reality in its multidimensionality but must deal with reality as if reality were multidimensional. However, a scientist should remain aware of what he does, if for no other reason than to avoid the pitfalls of reductionism.[9]

Due to the perspectival nature of knowledge, any knowledge is necessarily partial and limited. Reductionism is an ideological stance that ignores this partial limitation and presents its theory as one to which all other knowledge can be reduced. Frankl rejects reductionism and presents a multi-dimensional approach to psychiatric phenomena. I argue that such a multidimensional approach is applicable to all forms of knowledge.

The Multidimensional Approach and the Integration of Knowledge

As the term “unification” indicates, Unification Thought seeks the integration of knowledge. However, the term “integration” presupposes diversity. The multidimensional approach is necessary for two reasons: first, human understanding is necessarily perspectival or partial; second, the diversity of phenomena can be disclosed only through collecting such partial, perspectival expositions. Just as observing an object from multiple angles can reveal the three-dimensional reality of an object, a multidimensional approach can depict a complex diversity of phenomena.

Take the example of Joan of Arc, a 15th century French heroine known as “The Maid of Orléans.” She claimed to have received mythical visions and worked for France in the Hundred Years’ War against England. Although she was excommunicated and burnt at the stake by pro-English church authorities, she was later recognized as a saint by the Roman Catholic Church and canonized in 1920. From a religious perspective, she is a saint. From psychiatric perspective, she is schizophrenic. Viktor Frankl observes: “There is no doubt that from the psychiatric point of view, the saint would have had to be diagnosed as a case of schizophrenia; and so long as we confine ourselves to the psychiatric frame of reference, Joan of Arc is “nothing but” a schizophrenic.”[10] Frankl, however, also recognized her religious and theological significance.

As soon as we follow her into the noological (au. spiritual) dimension and observe her theological and historical importance, it turns out that Joan of Arc is more than a schizophrenic. The fact of her being a schizophrenic in the dimension of psychiatry does not in the least detract from her significance in other dimensions. And vice versa. Even if we took it for granted that she was a saint, this would not change the fact that she was also a schizophrenic.[11]

As discussed earlier, meaning arises from its contextual relationships. The same item or event can have multiple meanings according to its contexts. Consider how Joan of Arc’s mystical visions came to have historical meaning. If she had done nothing after having her initial mystical experiences, they would have remained only her personal experiences; and while they would have meaning within the context of her personal life, they would not have any social or historical significance. However, when her mystical visions guided her to a series of actions, they came to have new meanings in social and historical contexts. An assessment of Joan of Arc is thus carried out from multiple perspectives and contexts.

As Frankl rightly noted, each discipline has relative autonomy and integrity; thus, an assessment from one disciplinary perspective—in Joan of Arc’s case, the perspective of psychiatry—does not alter that from that of other disciplinary perspectives—those of religion, or French history. Thus, the integration of knowledge as envisioned by UT, will require a collaborative effort of multidimensional hermeneutics.

The quest for the integration of knowledge extends to a discussion about value. All human endeavors constitute the totality of social, cultural, and historical phenomena as the context and each disciplinary knowledge exists within multiple contexts. Due to the contextuality of human existence, the question of value necessarily underlies all human endeavors. The multidimensional approach, therefore, extends to disciplines that deal with questions of value such as ethics, axiology and religion.

Thus, Unification hermeneutics can be developed as a critical analysis of each discipline, such as the philosophy of biology, philosophy of psychology, etc., in order to highlight value dimensions in each discipline. The meeting ground of science and value is in the forum of philosophy, and UT can be developed as an integrated hermeneutics that incorporates discipline-specific philosophical analyses.

The Integration of Knowledge

As illustrated above, human knowledge is necessarily partial and demands a multidimensional approach. Forms of knowledge presented from multiple perspectives are not necessarily compatible and consistent. Some can be mutually exclusive and logically incompatible. There can be disagreements about methodologies, validation mechanisms, and assumptions. How can we integrate such mutually exclusive and logically incompatible knowledge? This question raises the possibility of a hermeneutic of hermeneutics.

I present the integration of knowledge as a guiding idea or the ideal that we strive for. No knowledge can claim to be the ultimate totality, including Unificationism. The Unificationist claim of the “unity of knowledge,” therefore, should be construed as an ideal for which Unificationism seeks.

This idea of the integration of knowledge has three desirable ends: first, it promotes collaboration among scientists and experts; second, it stimulates creativity for cross-disciplinary research; third, critical examinations from multiple perspectives help each discipline develop self-reflection and self-examination, thereby allowing each discipline to become more authentic. In other words, the integration of knowledge promotes the social value of collaboration, the intellectual value of creativity, and authenticity in knowledge.

Knowledge that is valid in one discipline is not necessary valid in another discipline. Validation must occur in each field. While collaborative efforts may create a new cross-disciplinary field, validation mechanisms still have to be established according to each field.

In addition, we must be extra cautious to see each theory apart from its philosophical assumptions. Some theories explicitly posit a philosophical worldview, and those who hold contrary worldviews may reject a theory on the basis of its worldview. For example, Freud and Darwin presented their theories together with their materialist worldviews. Some theistic scientists reject their views not on the grounds of disciplinary validity, but because of their worldviews. Although a theorist’s worldview may not be clearly separated from his/her theory, the discipline must assess the theory on its merits regardless of the worldview.

Further, the plausibility of a worldview does not necessarily validate theories built on a worldview. The plausibility of a theory, conversely, does not necessarily make its worldview truer. No single standard in a specific discipline has a privileged position. This shows a sharp contrast with the claim of Logical Positivism, popular in the philosophy of science in the early 20th century, which recognized physics as the foundational model of knowledge. The multidimensional approach is built on the recognition that there are multiple standards and each standard for validating knowledge is determined by its discipline. Although in each discipline there can be disputes over the standards for validating knowledge, such disputes should be settled within the discipline.

The multidimensional approach has the advantage of allowing one to see each theory in a specific discipline in relation to other theories in diverse disciplines. While each discipline has relative autonomy and independence, the implications of a given theory are examined with reference to a broader body of knowledge. For example, Freudian psychotherapy and Franklian psychotherapy have very different philosophical assumptions. Freudian theory is built on a mind-body dualist ontology with a mechanical, deterministic explanatory model. Frankl’s theory is built on a three-dimensional ontology consisting of body-mind-spirit with a freedom-based, non-deterministic challenge-and-response model. The differences of those two models can be examined in terms of their philosophical implications from philosophical perspective. In other words, a disciplinary knowledge can be seen within broader contexts of knowledge in a multidimensional approach. Such contextual shifts to new contexts of interpretation can generate new meaning.

Hermeneutics in Science and Religion

Why and how we can apply hermeneutics to diverse disciplines is still a question. Hermeneutics historically developed as a theory of interpretation in religion and law. Since religion and law require interpretation, hermeneutics is pertinent. Can we apply hermeneutics to science, the natural sciences in particular? I will show how the hermeneutical dimension of scientific theories came to be recognized in the history of philosophy of science. Although a hermeneutical dimension is present in both science and religion, hermeneutics works differently in science and religion. I will explicate this difference.

Hermeneutics in Science

Interpretation-fee knowledge was the ideal of many modern philosophers. From Descartes to Kant, modern thinkers tried to “liberate” human thought from Medieval, religion-based speculative discourse. One of their ideas was to strive for objective, interpretation-free knowledge, which they found in reason and empirical, experiment-based knowledge. They viewed tradition and authority negatively and held to the ideal of tradition-free, authority-free scientific knowledge.

In the history of the philosophy of science, the quest for prejudice-free, objective, interpretation-free knowledge was pursued in its clearest form by Logical Positivists in the early twentieth century. They presented the “verifiability thesis” as the criterion for the meaningfulness of knowledge: claims/statements are meaningful if their truth-falsity are determinable by science, and if not they are cognitively meaningless. They divided know-ledge into three categories: knowledge whose truth and falsity can be verifiable by science, formal knowledge such as logic and mathematics, and all other knowledge including arts, religion and ethics. The former two are cognitively meaningful, while the third kind of knowledge is cognitively meaningless and its value is limited to poetry.

To realize the unity of sciences, Logical Positivists took physics as the model science and attempted create a translation mechanism from other “fuzzy” sciences into the language of physics. They considered physics as the foundation upon which chemistry, physiology, psychology and other sciences were built.

Logical Positivism gradually faded from the dominant position in the philosophy of science for several reasons. First, scientific knowledge is built on assumptions that are not directly verifiable; what counts as “verification” is dependent on assumptions that are not verifiable.

Second, Karl Popper pointed out that scientific knowledge is open to change. He presented “falsifiability” as the characteristic of science as opposed to the “verifiability thesis” of Logical Positivists. Popper’s focus was to demarcate science from non-science. He pointed out that scientific knowledge is open to change and falsification, and such openness distinguished science from closed systems of non-science such as religions and quasi-religious theories such as Freudianism and Marxism.

Third, Thomas Kuhn pointed out that scientific knowledge has social, historical dimensions. Thus, scientific communities determine norms, standards, and other criteria of valid knowledge and validation processes, and scientific data is theory-dependent or theory-loaded. For example, “voltage” as a unit of measurement is meaningful only in reference to electro-magnetic theory; such “data” does not exist without such theory. He saw that contrary to the view of the Logical Positivists, scientific knowledge is much closer to other forms of knowledge and has hermeneutic dimensions. For this reason, Kuhn later rephrased his concept of “paradigm” as “hermeneutic core” and pointed out the affinity of knowledge in the natural sciences with that of the social and human sciences.[12]

Hermeneutics in Science and Religion: Objective and Transformative

There are different modes of understanding according to the degree of involvement of the cognitive subject and the object of understanding. Two distinctive modes of understanding can be described. In one mode, typical in religion, understanding arises through a transformative experience. For example, understanding the principles of Buddhist truth necessarily requires the existential transformative experience of the cognitive subject. One cannot detach the self from the principle of the world/cosmos depicted by Buddhism when one tries to understand it. One cannot simply objectify the subject of inquiry by bracketing the self as if one is a bystander. Enlightenment or compassion can only be comprehended by embodying it.

In the other mode of understanding, typical in hard sciences, you bracket the self and try to observe and deal with the object of inquiry without self-transformation. Who you are and how you exist are irrelevant. You can understand and speak about the truth as a bystander.

The distinction between these two modes of understanding stems from the relationship between the self and the object of inquiry. A degree of involvement of the self with the object varies from a discipline to discipline. Religions emphasize existential involvement, allowing for the observation of the transformed self; the sciences stress objective observation, minimizing the transformative dimension.

A Path toward Unification Hermeneutics

As I discussed, the integration of knowledge is an idea or ideal for which we can strive. Although I presented a multidimensional approach as a path toward this ideal, the task of developing the details of this approach remains. How Unificationism can contribute to such a task also remains to be explored. In this section, I present how Unificationism can contribute to the development of such hermeneutics. I articulate how Unification hermeneutics integrates approaches in science and religion. Although it is not a complete picture of Unification hermeneutics, it shows one possible integral method.

The Concept of Part-Whole as an Organizing Principle of Unification Thought: A Brief Overview

Hermeneutics takes a circular path. When a theory of interpretation is derived from a given body of knowledge, one is already carrying out interpretive action. This circular path is intrinsic to hermeneutics. Likewise, the task of deriving hermeneutics from the Principle is made possible by interpreting the Principle. Hence, the task is three-fold: first, to articulate how Unification hermeneutics is derived from the Principle; second, to show how Unification hermeneutics opens up a horizon or context of interpretation of the Principle; third, to use these hermeneutics to shed light on other bodies of knowledge.

One of the most basic principles of hermeneutics is the part-whole relationship. In UT, the concept of part-whole is the organizing principle of its ontology. UT holds two concepts of being: Individual Embodiment of Truth (IET) and Connected Body (CB). Under these concepts of being, UT presents the world as an integrally organized, mutually interconnected totality. These concepts of being are derived from the concept of part-whole: the concept of the IET views a being as a whole constituted by its parts; the concept of the CB views a being as part of a larger whole. Further, numerous layers of part-whole relationships make the world as a dynamic unity of numerous part-whole relationships.

UT’s creationist theism views the world as created by God. The concept of part-whole leads its creationist teleology to the concept of dual purposes, the “purpose for the whole” and the “purpose for the individual.” In other words, when the concept of part-whole is applied to the purpose of being, it makes it possible to distinguish purpose into dual purposes: “purpose for the whole” and “purpose for the individual.”

Two Approaches to the Phenomena of Truth in Unification Thought: Internal and External

UT’s integral approach appears in its attempt to characterize truth as the integration of science and religion. Exposition of the Divine Principle depicts religion and science as two methods that disclose “two aspects of truth, internal and external.”[13] This perspective resonates with two modes of interpretation, transformational and objective, which I discussed previously.

These two approaches, the transformative and the objective, present two orientations of hermeneutical activity. Each discipline has these two dimensions in varying degrees. As described previously, understanding in religion often entails an existential or a transformative experience, such as Enlightenment in Buddhism. Sciences generally take an objective approach. In particular, in the hard sciences, the self (experimenters/theorists) does not become existentially involved in the subject matter. Rather, truth is explored as an object by dissociating the self from the subject of inquiry. These two aspects of hermeneutics, the transformative and the objective, are present in varying degrees in each discipline. For example, in logotherapy or other therapeutic sciences, the realization of freedom in the self leads to a transformative experience for patients. At the same time, such disciplines seek objective principles that have transformative effects on patients.

These two aspects of hermeneutics, the transformative and the objective, work together in the social and human sciences. In the social sciences, we find a “double-hermeneutics,”[14] where social scientists interpret what are being interpreted. For example, when cultural anthropologists interpret taboos, norms, and rules of a targeted culture, they are trying to interpret what people in a given culture interpret. Although such interpretations by scientists do not involve an existential/transformative experience, it requires scientists to go deeper into what people in fact experience and comprehend. Scientists need to understand why and how their taboos, rituals, and norms make sense within the worldview of a given culture. In the humanities, in areas such as literature, art, music, and poetry, interpretation often requires some level of immersion, and a work may provide an inspirational or aesthetic experience; even if not truly transformative, it is hard to imagine the value of a work of literature devoid of any emotional or intellectual effects on the reader.

A Concluding Remark

Philosophy is a discipline that takes a critical stance and examines knowledge both within itself and outside of it. Through internal, critical analysis, it can disclose the hidden presuppositions and unnoticed philosophical assumptions of each body of disciplinary knowledge. Through contextual analysis, it can show the direct and indirect impact of knowledge within multiple contexts. We can examine its value dimensions when we see it within ethical, philosophical, even religious contexts. A multidimensional approach provides multiple perspectives for viewing a single body of knowledge, thereby opening up social, cultural, historical meanings.

A critical approach is opposite from a dogmatism that strives to turn its positions and claims into ideology. The danger of ideological intent is present in all disciplines from religion to the sciences. Although a critical approach does not exclude faith or conviction, it demands a critical stance upon itself and subjects itself to scrutiny through multiple perspectives. It respects and values the autonomy and integrity of each position, yet rejects the intent of ideological domination.

Unificationism is a theistic thought system deeply grounded in religious faith. If it strives for ideological domination over others under the slogan of “unity of knowledge,” that an ideal will never be achieved. Each religion or denomination tends to hold onto a claim of exclusive superiority over others. Many religions and their denominations hold such exclusivist convictions, and Unificationism is one of them. However, no matter how confident a religion is of its superiority, its horizon of understanding or context of interpretation is necessarily limited. Critical self-examination opens an opportunity to examine its framework of interpretation, unnoticed presuppositions, and social-cultural-historical conditions that shape the horizon of interpretation.

To realize the ideal of the “unity of knowledge” that Unificationism envisions as its ideal, I propose that its platform be a multidimensional hermeneutical approach. It can realize its ideal only through an ongoing, open process with the spirit of collaboration and mutual respect for others’ autonomy and integrity.

What, then, would such a Unification hermeneutics look like? It would be a multidimensional and integral hermeneutics which takes both the transformative and the objective approaches. The transformative and the objective generate a tension—the existential, experiential on the one hand and the critical, objective on the other.

There is also the socio-historical dimension of hermeneutics, not discussed in this article. Human understanding is always a dialogue between the socio-historical heritage of the past and our projection into the future. A Unification hermeneutics should have at least three components: the transformative, the objective, and the socio-historical. Through this multidimensional Unification hermeneutics, Unificationists can realize the possibility of achieving the unity of knowledge by taking a critical stance towards Unificationism and placing it on common ground with other fields of knowledge.

Notes

[1] This paper was presented at the 27th International Symposium on Unification Thought, July 21-22, 2017, Isshin Educational Center, Urayasu City, Chiba Prefecture, Japan

[2] “Distinctive Approach to Scientific Inquiry,” Purpose of ICUS, ICUS Org. http://icus.org/about/purpose/ (accessed April 4, 2017). ICUS started in 1972 and the 23rd ICUS was held in 2017 under the Universal Peace Federation. “World Summit 2017 Concludes with IAPP and ICUS Assemblies,” UPF. https://www.upf.org/conferences-2/364-world-summit/ 7334-world-summit-2017-concludes-with-iapp-and-icus-assemblies. (accessed April 4, 2017)

[3] For Rev. Moon’s interfaith initiatives, see “Rev. Dr. Sun Myung Moon, 1920-2012,” Universal Peace Federation. http://www.upf.org/founders /rev-dr-sun-myung-moon (accessed April 4, 2017). For his view of the unity of religions, science and religions, and knowledge, see Exposition of Divine Principle (New York: HSA-UWC, 1996), pp. 7-12.

[4] There are several works on Unification Thought. The latest and most comprehensive is: Sang Hun Lee, New Essentials of Unification Thought: Head-Wing Thought (Tokyo: Unification Thought Institute, 2005).

[5] The integration of knowledge has been a recurring theme in philosophy, from Aristotle in ancient Greek philosophy to Descartes in modern philosophy, and logical positivism in the twentieth century. Aristotle developed metaphysics, Descartes used geometry as the model, and logical positivists took physics as the grounding science.

[6] Ludwig Wittgenstein, P. M. S. Hacker, and Joachim Schulte. Philosophical Investigations (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2009), p. 43.

[7] Viktor Emil Frankl, The Will to Meaning: Foundations and Applications of Logotherapy (New York: Meridian, 1988), p. 9.

[8] Ibid., p. 10.

[9] Ibid., p. 30.

[10] Ibid., p. 14.

[11] Ibid., pp. 14-15.

[12] Thomas Kuhn rephrased “paradigm” as “hermeneutic core” to indicate the affinity of theories of natural science with social, human sciences in the presence of a hermeneutic dimension. See “The Natural and the Human Sciences,” in The Interpretative Turn: Philosophy, Science, Culture, edited by D. Hiley, J. Bohman, and R. Shusterman (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1991). The same essay is also included in Thomas S. Kuhn, James Conant, and John Haugeland, The Road Since Structure: Philosophical Essays, 1970-1993, with an Autobiographical Interview (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002).

[13] Exposition of the Divine Principle, p. 3.

[14] In the social sciences, scientists interpret what people interpret. This is called “double hermeneutics.” Anthony Giddens, a British social scientist, argues that it is a distinctive characteristic of social science in contrast to natural science which involves single-hermeneutics on the side of scientists alone.